In this post, I’m sharing how speech-language pathologists can improve aphasia outcomes by creating intensive home exercise programs. The majority of this content comes from Amanda Eaton (SLP, PhD) and Carmen Russell (SLP, PhD), who run an intensive aphasia therapy program at Fontbonne University near St. Louis, Missouri (with their approval).

I attended their seminar at the 2018 ASHA Convention, called “Creating Deliberate Independent Practice Programs for PWA: Insights from Intensive Therapies”. Their presentation was session 1084, in case you want to download their handout from ASHA’s Program Planner.

Free DIRECT download: Intensive home exercise program chart (patient handout). (Email subscribers get free access to all the resources in the Free Subscription Library.)

Outline of this post:

- Why should we assign intense home exercise programs?

- How intense should independent practice be?

- Tips for choosing therapy goals.

- Your plan should include three activity types.

- Developing activities.

- Set daily practice targets.

- Set an intentional schedule.

- Self-ratings and feedback.

- Trying it out with my first patient.

- Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts.

Why should we assign intense home exercise programs?

We have a big problem in the medical field when it comes to recovery from stroke. In general, people with aphasia (PWA) have far more potential for recovery than insurance will pay for. PWA can make progress for years, really for the rest of their lives, as long as they make the effort. We’re still learning what kind of effort is best, and how intensive that effort has to be in order to see real, meaningful improvement.

Here are the reasons why we should develop intensive independent practice programs (or home exercise programs).

- PWA have better outcomes from intensive therapy.

- As long as they continue effortful activities, PWA can potentially continue to improve for the rest of their lives.

- PWA are often discharged from speech therapy long before they’ve achieved their actual desired outcomes.

- Incorporating the principles of motor learning and neural plasticity with evidence from research will help bridge the gap between what insurance will pay for and what PWA actually need.

As home health speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and out-patient SLPs, we can play a huge role in setting people up for success over the long term.

First of all, we should:

- Support our patients in identifying one or two specific desired outcomes.

- Teach our patients how to turn their desired outcomes into SMART long-term goals.

- Devise multiple activities to target each goal.

- Set up an intensive practice schedule.

- Teach our patients how to monitor and reflect on their own performance.

Megan Sutton of Tactus Therapy has a great blog post on how to engage PWA and their loved ones in writing SMART goals.

Second, we should teach PWA how to identify their own goals, how to create a daily practice schedule, and how to select effortful tasks.

I would add that we should also teach PWA about online and/or community resources, including computer-based therapeutic programs such as Tactus Therapy apps, Constant Therapy, or Lingraphica’s TalkPath Therapy.

How intense should independent practice be?

Drs. Eaton and Russell stated that “purposeful intensive homework is how we can realistically achieve outcomes.” Here is what they suggest, based on research:

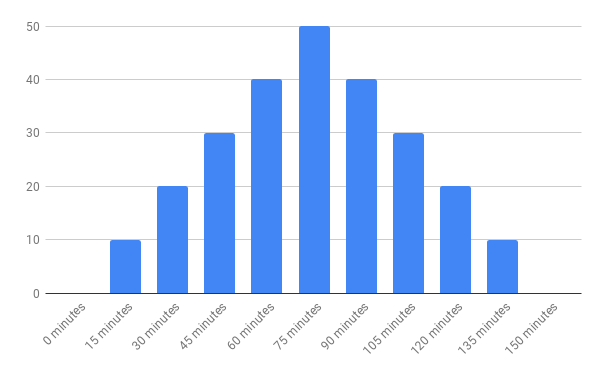

- 60-90 minutes of daily practice is a good target.

- Break this down into 20-30 minutes of focused attention and high effort.

- Take a break of at least 10-15 minutes between sessions.

- Complete one to two independent sessions on therapy days.

- Complete two to three independent sessions on all other days.

- Make sure patients understand that it must be effortful but doable. If it’s too easy, they won’t benefit. If it’s too hard, they’ll get frustrated.

Here’s a chart that you can show your patients, which is included in the free download.

The numbers along the left side don’t represent any specific data. The idea is that aphasia outcomes are better when people engage in an effortful home exercise program for 60 to 90 minutes just about every day.

Tips for choosing therapy goals

The presenters point out that aphasia is not a learning deficit. PWA can learn, but they may need more intensive training and practice. Here are their recommendations for developing goals:

- Assist your patient in identifying the goals.

- Then engage your patient in writing SMART goals.

- Focus on one to two goals at a time.

- Long-term goals should take three to six months.

- Short-term goals should take four to six weeks.

- “Mini” goals (specific therapy activities) should be achievable in five to 10 days.

- Goals should be written to be achieved independently or with minimal unskilled support.

Depending on my patient’s impairment level, progress in therapy, and insurance coverage, I may see my PWA anywhere from one to three months. This means that I’m likely going to be able to reach one or two “short-term goals” (they would be written as “long-term goals” in my report). Hopefully I’ll be successful in teaching my patient how to continue with their daily intensive practice so that they can reach their three-to-six-month long-term goals.

If we can teach people to set their own SMART goals and work towards them, then PWA could continue improving their skills indefinitely.

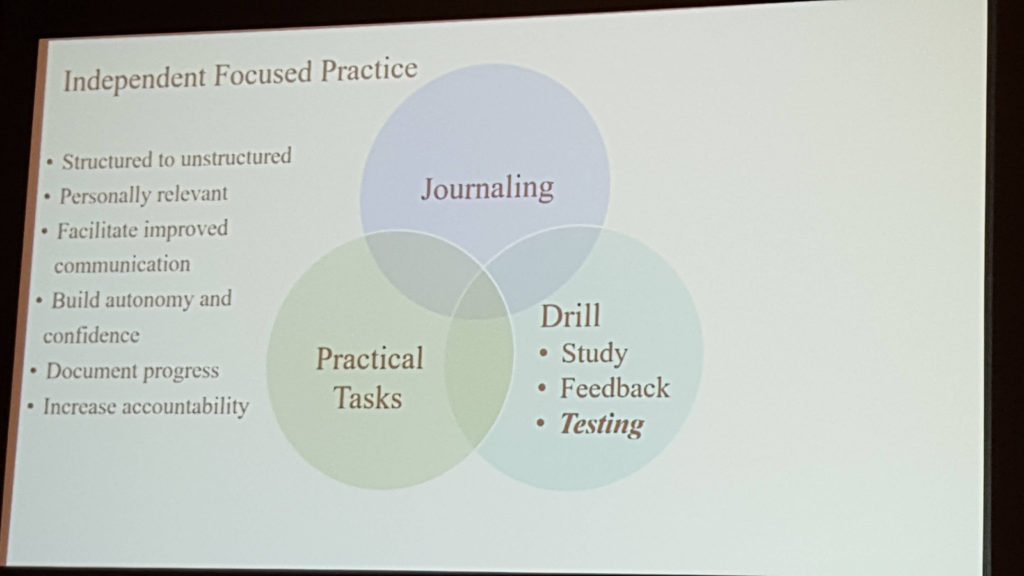

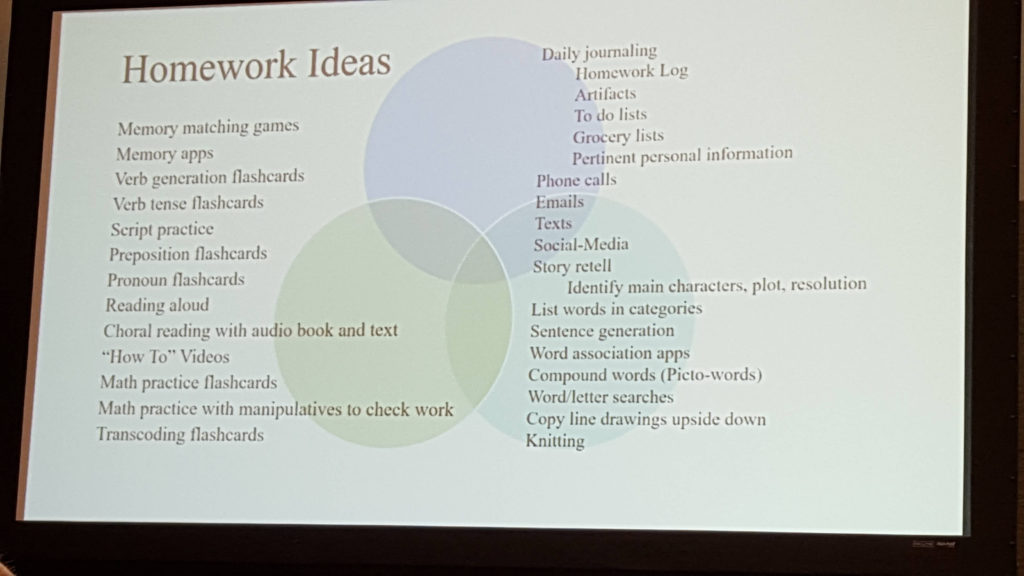

Your plan should include three activity types

The presenters suggest including a combination of three types of activities:

- Journaling.

- Practical tasks.

- Drill exercises.

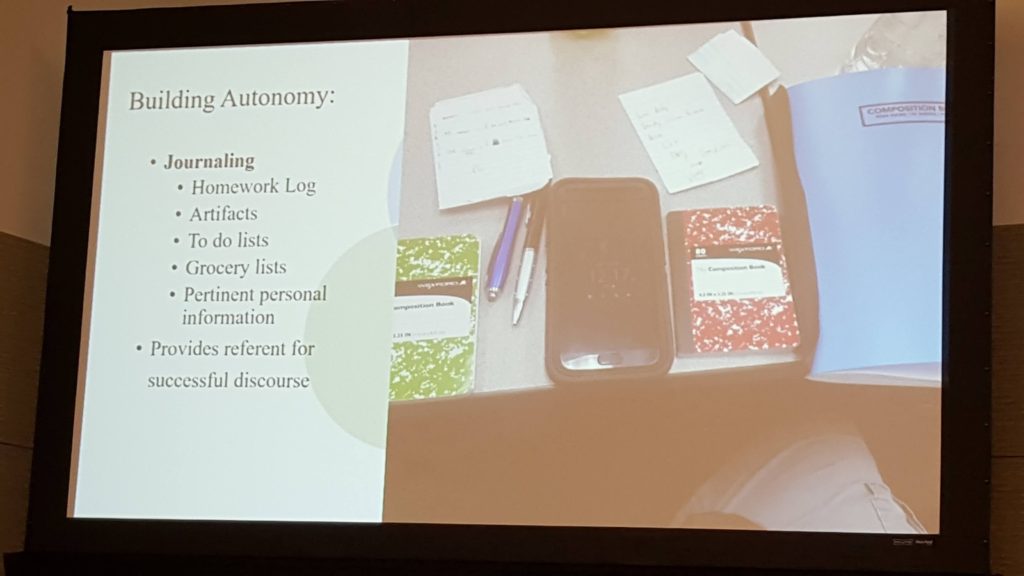

Journaling.

Journaling can be drawing or writing. It can be a single sentence about something that happened during the day, an answer to a writing prompt, or as long and as complex as the person would like. The book itself can be used for word retrieval during conversation.

Your patient can also include symptoms, vital signs, and questions for the doctor. The presenters suggest that our patients take their journals with them to doctor’s visits and write a brief summary of the outcome (or have a staff member write a note).

Other functional writing activities count as journaling, such as keeping a homework log, to-do lists, and grocery lists.

Practical tasks

Practical tasks involve any meaningful activity our patients engage in, such as reading the newspaper, responding to mail, arts and crafts, making out a shopping list, talking to family, etc. I think the idea here is to push the boundaries beyond what is easy and comfortable. The idea is to work harder in some fashion in order to do more.

Drill exercises

Use drill exercises to focus on specific speech, language or cognitive skills. Drill work should be time-based, meaning that your patient should work on the same activity until the scheduled practice time is up.

Drill exercises may include:

- Reading aloud or silently.

- Writing.

- Flashcard drills.

Reading, writing, and flashcards can be continued for as long as the practice session is. Based on the presentation I heard, it sounds as though the presenters don’t use worksheets because by nature they can’t be repeated until the practice time is up. They don’t want to give stacks of worksheets to their patients.

Join Fontbonne University’s Aphasia Group in Quizlet for free access to flashcard sets

The presenters often use Quizlet for their drill exercises. PWA can access pre-made flashcard sets, or new flashcard sets are added as needed. Dr. Eaton has graciously extended the offer to all of us to join their Aphasia Group in Quizlet to access, copy, and use their flashcard sets.

Frequent testing is important for learning

Incorporate frequent testing into your drill exercises. Testing offers many benefits, including:

- Enhances learning.

- Promotes autonomy.

- Improves awareness.

- Increases accountability.

- Provides encouragement.

If you use an app such as Quizlet, testing is built in. Otherwise, you could teach your patient how to test themselves by providing a quiz and an answer key. Or a family member could test your patient.

Developing activities

The activities you choose may be speech, language, or cognition. We know from recent research that PWA also generally have impaired attention or memory. The presenters stated that “when you strengthen one skill, the others get better too. The brain is a network.”

- Choose personally-relevant materials and tasks.

- Find Goldilocks tasks: easy enough to be completed on own (or with minimal unskilled support) but hard enough to require real effort.

- Design open-ended activities instead of completion-based task. Create activities that the patient can do over and over for the scheduled period of time. The presenters don’t use worksheets.

Vary the context

By varying the context, you can improve generalization and transfer of the skills. For example, your patient may choose to focus on pronouns, since using the wrong pronoun may be embarrassing. Your drill work may include these different activities:

- Producing simple sentences each containing one pronoun.

- Highlighting pronouns and referents in a text.

- Matching pictures with pronouns.

I’ll talk more about the practice schedule below, but on most days, a 20-30 minute session would consist of only ONE of these exercises.

30 activity ideas

Set daily practice targets

First, select one or two SMART short term goals and break each one down into mini-goals. The mini-goals correspond to specific therapy activities. Then work out which activities will be completed on which days and for how long, following the principles below. Teach your patient how to do this, so they can continue after you discharge.

Then set daily practice goals of two to three practice sessions of 20-30 minutes each (plus skilled intervention sessions).

Then teach your patient to record their activity and progress in a homework log or journal. Be sure to encourage self-reflection and celebration of achievement.

Set an intentional schedule

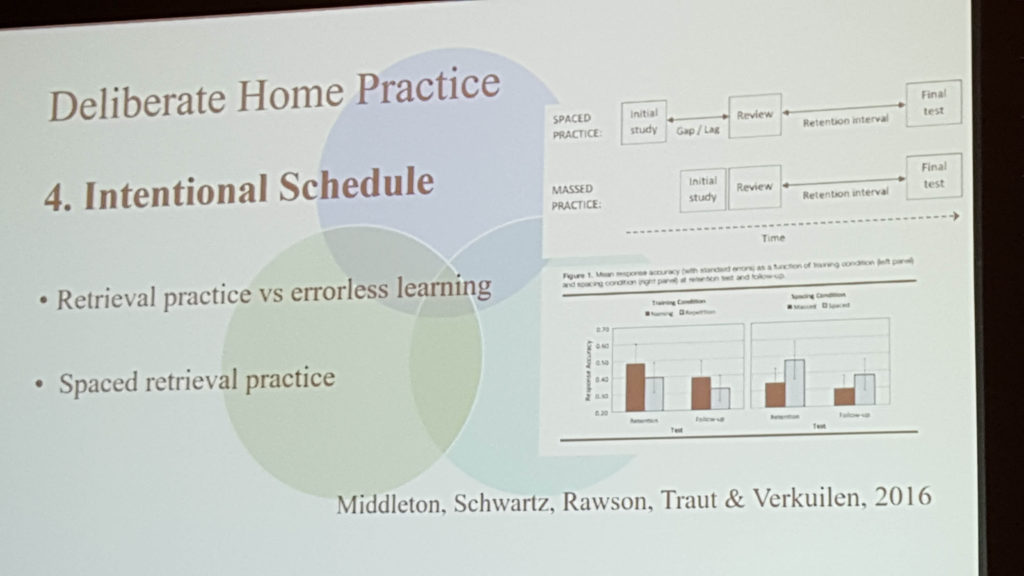

The presenters admit that the schedule I’m about to share is elaborate, and they said we don’t have to go to these lengths. If we don’t we should still follow the general principles. Take a look at the slide below.

- Retrieval practice vs errorless learning.

- PWA don’t have a learning impairment, so effortful retrieval is better than errorless learning.

- PWA should engage in high-effort work to retrieve words.

- Spaced retrieval provides better results than massed practice.

- Spaced retrieval refers to a time delay between initial study, review, and the final test. Your patient should practice the target skill with different activities on different days.

- Massed practice refers to not having a delay between initial study and review. In other words, your patient shouldn’t practice the same activity every day for a week.

- If you consider the content of a single session, massed practice is helpful at the very beginning, but spaced retrieval is better for retention over the long run.

- In other words, in the beginning, your patient could spend 3 entire consecutive days on a single activity, then switch to a new activity on day 4, and then on day 5 would split the time between the two activities.

- Both activities should target the same goal.

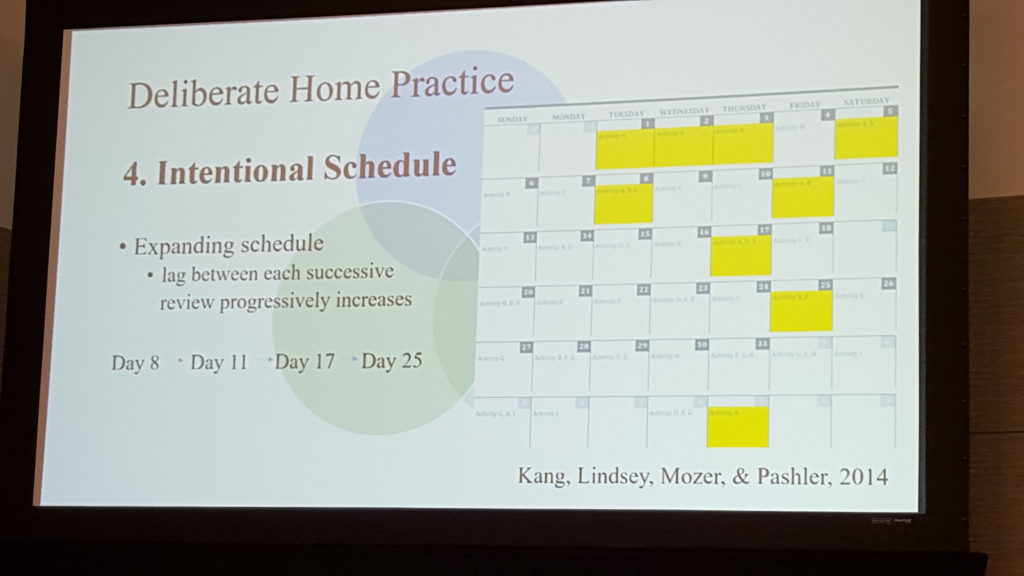

A sample schedule

Now let’s take a closer look at a sample schedule. My apologies that the following slide isn’t very clear. I’ll replace it, if and when their presentation is uploaded to ASHA’s website.

This picture is hard to read, but this calendar assigns nine different activities (Activity A through Activity I). These activities may target one or two short-term goals. Activity A is highlighted in yellow on each day it is practiced.

You can see that Activity A starts off with massed practice. The first three days are solely practicing Activity A.

Then Activity A starts to get distributed. Day 4 is devoted entirely to Activity B. Then each session on Day 5 would be divided between Activities A and B. Day 6 is Activity B. Day 7 is Activity C. Each session on Day 8 is split between Activities A, B, and C.

The schedule continues, introducing new activities as older ones become more distributed. A day of rest is scheduled about every two and a half weeks.

Evidence-based principles of intentional scheduling

Remember, the presenters said that we don’t have to be so elaborate in our training schedules. But we should keep the key points in mind:

- Focus on one or two specific short-term goals at a time.

- Create a variety of activities that target each goal.

- Teach our patients to follow a daily, intense practice and to monitor their practice.

- Start off focusing on one activity two to three times a day for a few days.

- Then start a new activity targeting the same goal.

- Interleave the two activities for a few days.

- Then start a third activity targeting the same goal (and continue in this way).

I think if I were going to target two specific goals in the same month, I would assign Activities A through E to one goal and Activities F through J to the other.

Typically, we can’t keep patients on our caseload to work through all of the long-term goals that they are likely to have. But we can teach them to direct their own independent practice according to evidence-based principles, and this will benefit them for a lifetime.

Self-ratings and feedback

Encourage your patient to reflect on their own performance to improve self-monitoring skills. If the presenters went into detail on this, I missed it. But I think your patient could use the rating scales to:

- Predict how they think they will do on an activity.

- Reflect how they think they did on the activity.

- Show how they actually did on an activity.

Making a prediction or judging your own performance before learning how you actually did can be very enlightening.

There are many self-rating scales available. I’d have a few handy and try them out with my patient to see which one they liked. Your scale could be picture based (faces), number-based (scale), or word-based (poor, fair, ok, good, excellent).

Providing feedback is important as well. I’d initially provide a lot of feedback on their performance but then hold back and encourage my patients to judge their own performance. My goal is to improve their self-monitoring skills. The presenters also stated that we should provide ongoing feedback regarding their progress towards reaching the goal.

Trying it out with my first patient

I’ve decided that I’m going to use this approach with any PWA who wants to improve their speech, language, or cognitive-communication skills. I’ve been working on this post all week, and it feels both interesting and a little intimidating. I was having trouble imagining where I would find the time. (Spoiler alert: It went very well, and you can read the outcome here!)

And yet today, I met someone who is a year post-stroke. He’s had speech-therapy for the past year with little improvement, but he’s had some medication changes over the past month and he’s becoming more verbal (putting together two and three word phrases).

Today, he responded well to Response Elaboration Training, and as a first pass at developing this intensive program, I used the chart above to educate he and his wife that the target is 60 to 90 minutes of daily effortful practice. I provided a month-view calendar page and drew in 3 small squares for each day. I told them that each box represents 20 to 30 minutes of speech practice. When they complete the practice, they’ll fill in the square.

His wife is going to assist him with talking about his memorabilia using RET strategies for his speech exercise. I believe this would count as a “Practical Task.” I’ll come up with some other activities of interest, including some drill work, and then try to follow a practice schedule like the example one above. He’s not interested at all in using an iPad or computer, so I won’t be able to use those tools.

What I did with this person today was very easy, took no more time than anything else I would have done, and now they will be using an evidence-based therapy approach to target his strongest desire (to be better at conversation) in an intensive fashion. I’m excited to see how it goes!

Give intensive home exercise programs a try, and let us know how it works for you.

Related Eat, Speak, & Think posts

- How intensive home exercise helped my patient talk again.

- Free course to improve conversation skills in aphasia.

- Free multimedia resources for the SLP.

- Attentive Reading and Constrained Summarization tutorial.

- My patient improved conversation with ARCS.

Free DIRECT download: Intensive home exercise program chart (patient handout). (Email subscribers, access in the Free Subscription Library.)

Lisa earned her M.A. in Speech-Language Pathology from the University of Maryland, College Park and her M.A. in Linguistics from the University of California, San Diego.

She participated in research studies with the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the University of Maryland in the areas of aphasia, Parkinson’s Disease, epilepsy, and fluency disorders.

Lisa has been working as a medical speech-language pathologist since 2008. She has a strong passion for evidence-based assessment and therapy, having earned five ASHA Awards for Professional Participation in Continuing Education.

She launched EatSpeakThink.com in June 2018 to help other clinicians be more successful working in home health, as well as to provide strategies and resources to people living with problems eating, speaking, or thinking.

HI Lisa,

This website is amazing!

I work at Texas Health Fort Worth as the SLP coordinator for inpatient and outpatient services. I tried to find the aphasia outcome scale used by the aphasia clinic at the former Rehab Institute of Chicago but have never received access to it. We have been asked to ‘show’ progress every 10th visit for all disorders including aphasia. We are close to getting NOMS activated in our electronic health record but even it is hard to show progress with that scale every 10th visit. We have the FCS, ASHA FACS, Ceti (which is more for the caregiver). What do you all use?

Thank you !!

Beth

Thanks so much, Beth! Working in home health, I’m on a 30-day schedule. I use the WAB-R, BDAE-3, and the BNT-2. I also recently downloaded the Quick Aphasia Battery which is free (http://aphasialab.org/qab) and the Aphasia Impact Questionnaire (AIQ-21) which asks for a donation (https://www.aiq-21.net/). Showing progress every 10 days would be tough. If the person is experiencing improvement within 10 days, then the AIQ-21 would possibly reflect that. Actually, I think that if the person is making noticeable progress in verbal expression in a 10-day period then discourse measures would show progress. There are objective discourse measures that you can calculate from a language sample, although I’m not aware of a “test” per se.

Hello,

Just wondering if you know of the evidence for this program with patients with progressive conditions (e.g. PPA, vascular dementia, GBM)?

Hi Vanessa,

Great question! If Professors Eaton and Russell have applied this program to people with progressive conditions, I’m not aware of it. They would probably be the best people to ask. It should be relatively easy to find their email addresses with a search. They are at Fontbonne University near St. Louis, Missouri. (I don’t want to share their email addresses here.)

Thank you for the reply! I will definitely reach out.

Hi Lisa,

This is such a great post – so much to think about and implement. Thank you for your practical example at the end – it’s very helpful.

Just wondering, in terms of the spaced retrieval practice is that largely referring to the drill tasks or is that all three activity components (journaling, practical tasks, drill).

Thanks 🙂

Thanks, I appreciate that! I think spaced retrieval would work for all three activities. For instance, rather than sitting down to journal for 2 hours on a Saturday morning, break that up and do 15+ minutes of journaling each day.